The most brutal of the mechanistic treatments from the 1930s

Lobotomy, a form of psychosurgery was also introduced in the 1930s. The most brutal of the mechanistic treatments, lobotomy seems to have gone largely unregulated in the UK, when as late as 1951 Dr M J Mannheim wrote to the British Medical Journal in these terms. “desperate cases require frontal leucotomy under strict safeguards which so far do not exist”. He goes on to say, “Many colleagues are profoundly disturbed that we have entered into an era of violence in psychiatry”. This surgical procedure separated neural pathways in the frontal lobes from structures deep in the brain.

The first experimental brain surgery had taken place as early as the 1880s when a physician, Gottlieb Burkhardt, removed part of the cerebral cortex from patients in his care in a Swiss mental asylum. It may be worth recalling one definition of the word ‘asylum’ as a place of refuge and safety. Not so for several of Dr Burkhardt’s patients who died within days of the surgery.

It wasn’t until 1935 when two Yale physiologists, Carlyle Jacobsen and John Fulton presented a paper at the Second International Congress of Neurology in London, that the idea of using surgery to alleviate mental illness took off again. They described how removing the frontal lobes of a chimpanzee had made it more cooperative and willing to perform tasks. Lobotomy began to be prescribed for mental illnesses including depression, mania, schizophrenia and obsessive compulsive disorder.

Egas Moniz, a Portuguese neurologist had already developed a theory that insanity was the result of fixed ideas that were maintained by established neural pathways in the prefrontal lobes of the brain. He believed that by disrupting these neural pathways the symptoms of mental illness could be relieved. Jacobsen and Fulton’s findings seem to have prompted Moniz to carry out the first lobotomy on a human being, a sixty-three year old woman suffering from depression, anxiety, paranoia, hallucinations and insomnia. “I decided to sever the connecting fibres of the neutrons in activity” he later wrote. Moniz was assisted by Portuguese surgeon Pedro Almeida Lima who drilled two holes in the woman’s skull and then injected ethyl alcohol into the prefrontal cortex in order to destroy brain tissue. Although this first surgery was considered to have been a success, Moniz and Lima went on to develop another technique which also involved drilling two holes into the skull, either at the top or sides of the head and pushing an instrument called a ‘leucotome’ into the brain.The surgeon would sweep this from side to side, severing the connections between the frontal lobes and the rest of the brain.

As is often the case with psychiatry’s pioneers, Moniz reported dramatic improvements in his first patients and lobotomy was eagerly taken up by Dr Walter Freeman a neurologist who performed the first lobotomy in America in 1936. Together with neurosurgeon James Watts they developed a standard operation, the Freeman-Watts prefrontal lobotomy. But that wasn’t enough for Freeman and in 1945, building on a technique piloted by Italian surgeon Amaro Fiamberti, he developed a procedure called transorbital lobotomy. The orbit in question was the eye socket, and an instrument called an orbitoclast which sounds terribly specialised but is in reality very like an icepick, was inserted under the eyelid, over the eyeball and hammered though the thin layer of bone at the top of the eye socket. The sharp point of the orbitoclast was pushed into the frontal lobe and twirled around to sever the connections between the frontal lobe and the rest of the brain. If you think you can stand it, you can find photos and footage of this atrocity actually being carried out on several websites.

At one stage Freeman lobotomised 228 patients over a twelve day period for the West Virginia Lobotomy Project and once lobotomised 25 women in a single day. One wonders what was going on in Freeman’s head as he drove around America performing conveyer belt lobotomies. Aside from the people that he wrecked, 14% of Freeman’s patients died and that was the fate of Freeman’s final patient, a woman who had a fatal cerebral haemorrhage during her third lobotomy operation and brought Freeman’s career to a close.

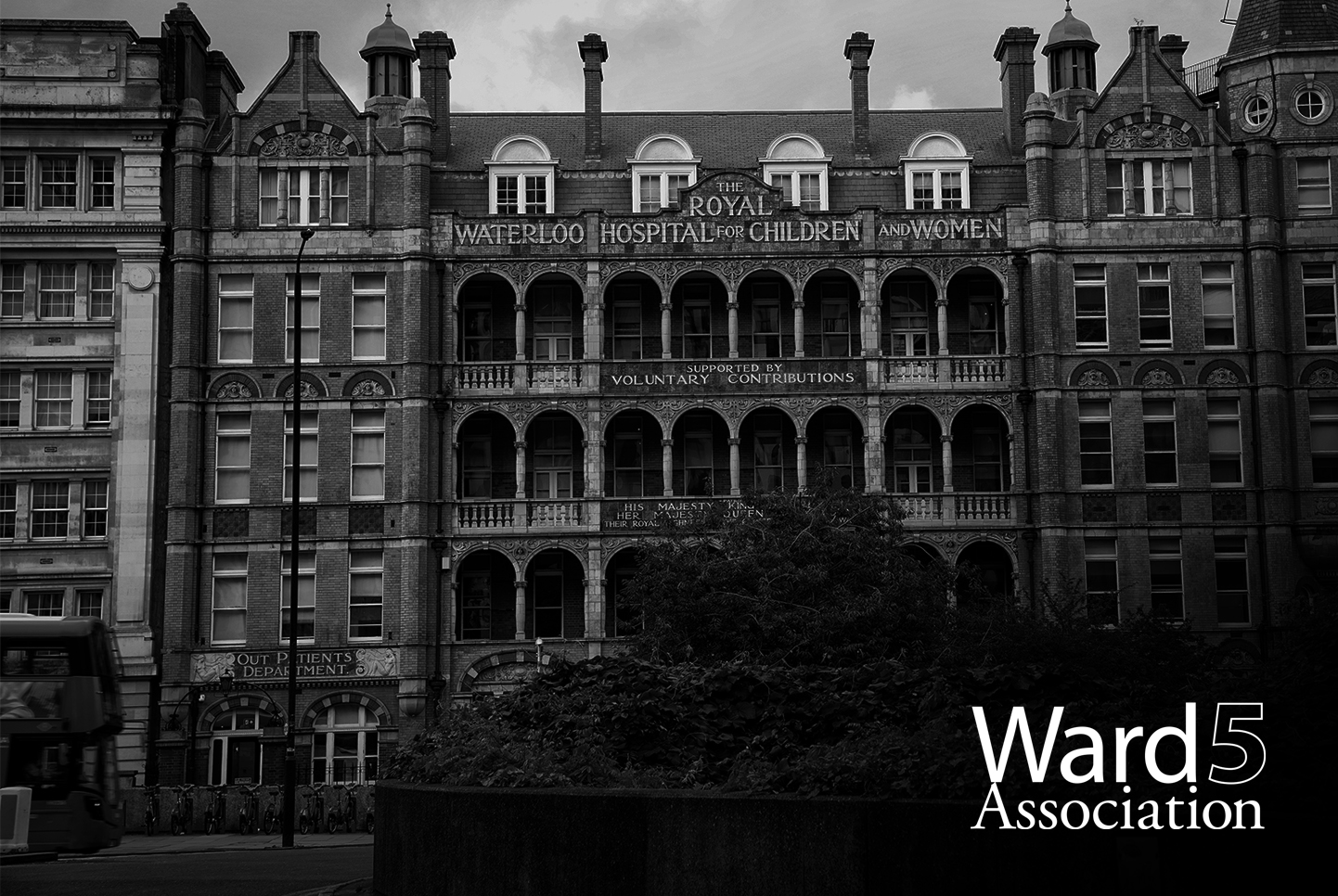

Clearly, Doctors Sargant and Pollitt were worthy successors to the medically qualified madmen of the 1930s who would have applauded the development of Modified Narcosis as it was carried out at The Royal Waterloo Hospital between 1964 and 1973.